The questions we ask

The quest for generality is at the core of ecology. Once we observe some relationship between X and Y, we usually want to know how general that relationship is, and how much the relationship can vary in different conditions – whether it’s ecosystems, species, individuals, sites, or other groupings. In other words, we are interested in separating the variation we observe into (1) a general relationship between X and Y that explains what we see most of the time, and (2) conditions under which this general relationship may differ. These conditions can be ecological (i.e. maybe species differ in the way they respond to X), but they can also be due to the process of observing the relationships (i.e. maybe X responds to Y in site A as expected and B but not C and D, for reasons we haven’t measured).

As an example, we know that plants generally grow faster when they are exposed to more light. If we go out and measure plant growth rates in sites A, B, C, and D, we may see that this general relationship holds. But, some species may actually grow better in low light, and their relationship with light will differ.

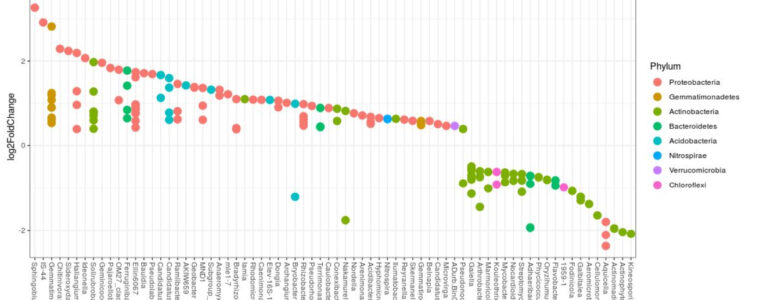

When we monitor biodiversity change, we are often asking a similar question. How are species’ abundances generally responding to global change: are they declining? stable? Growing? Once we know this general response, we also need to know how individual species are doing: which species are declining the fastest, and need immediate conservation interventions? Which ones are stable but not growing, but should continue being monitored in case this changes? Which ones are growing, and may be doing better after conservation or may not need any conservation action for the time being?

So, our question is generally framed in this way: what is the general relationship, and when and how much can this relationship differ between species?

How we answer these questions

To answer these questions, we build models, collect data, and evaluate how well our model explains the data. For simplicity, let’s explore an example where we want to understand Y ~ X for many species. One approach is to model Y ~ X for each species and then try to put all these models together to get some kind of average or agreement between them. Maybe we could look at how the slope of our models vary across these species, to make inferences about how the strength of the relationship between X and Y differs between species.

Another approach is to build one model that disentangles the Y ~ X relationship into a general component, which summarises the general trajectory for all species, and a species-level component, which estimates how the relationship of Y ~ X is conditional on species identity. This is, essentially, a hierarchical model: we are estimating variation (1) across species, and (2) between species in one model.

Which comes first? The chicken or the egg?

Over the last decade, we’ve seen a burst in modeling capacity in ecology. We have big datasets, more powerful computers, a wide catalogue of statistical modeling tools and literature to back it up, and importantly – a ton of questions we want to answer.

These questions should, of course, always be based on our previous understanding of relationships we’ve studied between Y and X from the literature and our observations of nature. Our questions are supposed to shape the model we build – but, we have to admit that sometimes the model shapes the question first. Maybe our labs use certain models that we’ve adopted ourselves, and we find ways to apply this model to new datasets. Maybe our field loves using a certain approach (like community ecologists love a good PCA – no shame here, I love a PCA too), so we reach for it first. Maybe we think a newly published modeling approach is fancy and cool, and want to find a way to use it in our research. These are all fine, honestly.

But we are wondering: Are our research questions sometimes limited by our model “comfort zone”, and if so, how do we push past this?

In other words, like the chicken and the egg: Which came first, the question or the model?

Are there questions that we aren’t yet asking because we don’t know how to answer them? Are some of these questions actually possible to answer now that we have an abundance of models, types and sizes of datasets, and powerful computers?

Join a community call!

If you’re interested in talking more about these models, please join our community calls during March and April 2025! We welcome anyone interested in GAMs, computational ecology, or eager to learn more about HGAMs to participate in the following sessions:

- Temporal Ecology with HGAMs

When: March 7, 2025 at 1:30 PM (EST)

Registration: https://us02web.zoom.us/meeting/register/eocqFUC7QZG9HqydWb2Lsw#/registration - Spatial Ecology with HGAMs

When: March 14, 2025 at 1:30 PM (EST)

Registration: https://us02web.zoom.us/meeting/register/BAdUd6hKSDmzG_w4hgbgrQ#/registration - Behavioural Ecology with HGAMs

When: March 24, 2025 at 1:30 PM (EST)

Registration: https://us02web.zoom.us/meeting/register/taVdATjWRw2uhzYTry2bHA#/registration

These community calls are intended to help us face this question. Each discussion will focus on the outstanding ecological questions that we could answer with HGAMs, highlighting a wide array of potential applications for specific types of ecological and evolutionary data. Join us in thinking about how we could use HGAMs to push ecological research forward! You do not need any background with hierarchical modeling or generalized additive models to join these discussions.

Each discussion will follow this structure:

| Activity | Duration |

| Welcome & Scope | 10 mins |

| Individual reflection before the small group discussion | 5 mins |

| Small group discussion: What question do you usually ask? What question would you like to ask next?What model(s) do you use to answer your questions? Are some of your questions (or questions you’d like to ask) something you could ask with a hierarchical model, or hierarchical GAM? | 15 mins |

| Whole group discussion (discuss the small group findings) | 25 min |

| Wrap up & next steps | 5 mins |

| Close | – |

What is this all for?

Our intention is to collaboratively write a Perspective paper to highlight the outstanding questions in ecology that could be explored with hierarchical GAMs.

Please fill this form to let us know how you would like to participate (or not) in the next steps.

All participants of this call who contributed to the notes and discussions will be credited in the acknowledgements of the paper unless otherwise communicated to us.

Authored by Camille Lévesque and Katherine Hébert